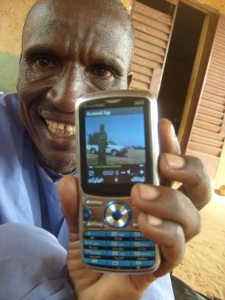

Ahmadou’s first call to me (in Holland) via mobile telephony was in 2007. He called from this ‘remote’ place in Central Mali where until that time telephone connections were impossible. Ahmadou had never traveled further south than Douentza. Only in 2012 he traveled to Bamako, the capital city of Mali, to visit me there as it was impossible for me to go to Douentza or Boni because of the conflict and chaos in the region at that time. Anno 2015 he is a regular traveler to the south, involved in politics around the conflict, and he calls me at least twice every week. Ahmadou’s life has changed profoundly both as a consequence of mobile telephony and of the 2012 conflict.

I have doubted for a long time whether I should present Ahmadou as a counter voice in this blog. Ahmadou is an old friend. He herds our cattle in the Seeno, that is the southern part of the 2012 occupied zone, then called Azawad. Ahmadou and his family became deeply involved in the conflict despite themselves, but irreversibly so. Ahmadou’s role as a leader in these changes has turned him definitively into a counter voice. I described the (re) union of the Fulani nomads in a former blog. And it did not stop there.

A simple herder…

A simple herder…

Some background information about Ahmadou: he was born around 1960, we are age-mates. We first met in 1990, when I started (together with Han van Dijk) an ethnographic research in Serma, the hamlet that also serves as a meeting and service point for the nomads during the rainy season, when they work their millet fields. In November, after the harvest, many nomad families leave the region to search for pasture areas further away. Ahmadou’s father was our host. We got to know the family well and when we finished the PhD research we decided to buy a cow to establish a long relationship with the family. And that is what happened. Friendship and cows are intimately related in Fulani life. Ahmadou’s father passed away in 2010 and Ahmadou became head of the family; together with his brothers he continued to manage the family herd (including ours). Ahmadou married two wives. He has 8 children. One son (the eldest son of his second wife) was sent to the Koranic school, quite a rare decision for nomad’s children. The other sons herd cattle and camels and work the fields during the rainy season. His daughters have all married within the family group. They continue to live close to each other. Ahmadou’s mother lives with him, her eldest son. So far Ahmadou’s life is the life as expected from a Fulani man, except for the son in the Koranic school.

…or a leader?

Ahmadou also took another decision in his life. His father was head of the family group, responsible for administrative matters, and mediator in case of conflict. Ahmadou followed his father’s path and also became lineage leader. He took his task a little heavier than his father had done and developed into a politician, with good relations with representatives of different parties, who he called regularly. Finally he chose to follow one of the opposition parties. Here, he deviated from the Fulani elites. In that period he also bought land in Boni (the town near his rainy season camp) to build a house. His aspirations were changing. His son in the meantime returned from the Koranic school as a Muslim teacher (Mallam). Gradually Ahmadou positioned himself as more than a lineage leader, he became intermediary to national politics, and also developed ideas that went beyond the ideas of the Fulbe elites, whom he increasingly considered extensions of the State. He did not expect any good from the State that for him represented basically oppression and impossibilities: the forest service did not allow them to exploit the resources they needed, the hospitals are far away, the police acted against them, etc. Ahmadou was reinforced in his idea that the Malian State was not really ready to support the Fulani nomads, and he did not expect much help from the Tuareg. He experienced the presence of MUJAO (a Jihadist group) as more protective and providing security than the others.

In that atmosphere Ibrahim Moodi approached him in 2012, to help him establish a movement of the Fulani nomads. At the same time he realized that joining the jihadists would not be a good future, hence he embraced the idea for the Fulani nomad’s union and became one of the leading figures in that meeting and organization. The meeting was held in autumn 2014, and afterwards he and two others (among whom Ibrahim Moodi) went to Bamako to meet with UN, EU and others. They returned to Boni with some hope, but when nothing was done for them, they became a little desperate. Instead of any help, they experienced increasing insecurity, criminality, and in fact complete absence of any security in the region. Other Fulani groups started to organize themselves in self-defence groups (see short vodcast made by Boukary Sangaré). Ahmadou and Ibrahim kept quiet and continued to believe in a dialogue.

In that atmosphere Ibrahim Moodi approached him in 2012, to help him establish a movement of the Fulani nomads. At the same time he realized that joining the jihadists would not be a good future, hence he embraced the idea for the Fulani nomad’s union and became one of the leading figures in that meeting and organization. The meeting was held in autumn 2014, and afterwards he and two others (among whom Ibrahim Moodi) went to Bamako to meet with UN, EU and others. They returned to Boni with some hope, but when nothing was done for them, they became a little desperate. Instead of any help, they experienced increasing insecurity, criminality, and in fact complete absence of any security in the region. Other Fulani groups started to organize themselves in self-defence groups (see short vodcast made by Boukary Sangaré). Ahmadou and Ibrahim kept quiet and continued to believe in a dialogue.

Shocking April 2015

Shocking April 2015

Their trust in a future was crushed by the events of April that really left all in shock. On 1 April the police were attacked in Bulli Kessi, the village of Ibrahim Moodi. As a counter act the police (most probably afraid for Jihadists) killed three young Fulani men, who were accused of being Jihadists. Shortly after, on 3 April, the police, this time in Boni, were attacked again and two civilians got killed. On 7 April the gendarme/police came to Serma where they arrested 18 men, among whom were Ahmadou, Bura (secretary of the Fulani movement), and some young men, who they all accused of being Jihadists and possible attackers of the police. On 11 April Ahmadou, Bura and three of the young men were transferred to the prison in Sévaré/Mopti. The others had paid considerable sums to be free. In Sévaré they could hardly communicate with the authorities, nor with the police (language barrier), and they did not in the least understand why they were arrested. They had nothing to do with these attacks and tried the dialogue way; also, they were convinced that it is better to keep out of the Jihadist movement. The arrest was experienced as a violation of their rights; the deaths of the three young men in Bulli Kessi as a direct attack on the Fulani nomad community. After negotiations and no clear evidence against them, they were allowed to leave and headed back to Boni/Serma. Intervention by MUNISMA (the UN mission in Mali) led to the replacement of the policemen by ‘northerners’. MUNISMA and the European Union did send a humanitarian mission to do research on the situation, also after alert mails from Boukary, Han and myself. The Fulani-case is taken very seriously by these organisations. They should regret their lack of action after the call of the Fulani leaders last November, though. (More about the April events in this article by Boukary Sangaré.)

Fighting for his people

When Ahmadou called me last week from Bamako, where he was to ‘arrange’ all kinds of things, he made it clear to me that the replacement of the policemen was indeed an improvement: he could at least communicate with these men, but in order to keep them as friends he had to ‘pay’ them. Order had returned somehow. Nevertheless, he did not trust the situation: another attack against them could be expected soon; he also suspected his elites to be behind all this, as they are in league with the Malian State. The beginning of a trust relationship that Ahmadou and Ibrahim had tried to establish crumbled to nothing. Ahmadou now felt obliged to come to Bamako, to fight for an honest treatment of his people, leaving the cattle in the hands of his sons, despite the bad quality of the pasture this year. It has certainly become clear to him that he cannot expect any substantial aid and support from the Malian State.

Mirjam and Ahmadou in 2012.