Protest in Bamako 5 April 2019, @bbc.co.uk

Many thousands of people have been protesting on Friday 5 April 2019 in the capital of Mali, Bamako. It was massive. Also in Bandiagara, Bankass people went to the streets. Earlier protests in Paris, and elsewhere in the world were organized where people expressed their worry about a possible horror scenario in the Sahel. Mali is at the centre of these worries, but many make allusion to a much wider problem. The killing of 170 people in three villages near Bankass on the 23rd of March is the immediate reason for the protests in Mali. The Ogossougou massacre will be forever part of the history of Mali and the Sahel.

Violences

I was in Mali on this 23rdof March, living the horror with my colleagues of a research team doing research on political developments in Mali, with all Bamakois and with myself. Most of the killed people were innocent Fulani pastoralists among who were some who fled the horror of earlier troubles around another village in the Koro district. Beginning this year another deadly attack was in Koulogon also near to Bankass, where 37 people found their death. These attacks reach the international press, but many smaller attacks are hardly noticed not even within Mali and are a daily phenomenon for almost two years now. Not only Fulani pastoralists but also sedentary farmers of other ethnic groups in the region are victims. The killings on the Fulani seem to be higher in number, but we cannot be sure because they are also more mediatized. One of the problems is that we do not have information about what is exactly happening. We spoke with displaced Dogon and Fulbe in the South of Mali (near Bougouni) and in the Capital city Bamako and their stories are all equally horrible.[1]

Discussing the situation with displaced Dogon in a village near Bougouni @Mirjam 2019

Multiple Emotions

Certainly the underlying causes for this situation are multiple. We already touched on some of these in other blog posts. Making a sound analysis is almost impossible to do now, soon after these events and with the turmoil in my head. It is important to take a distance first from my own emotions.

Therefore I decided to write this short blog to warn against fast interpretations of these violent events in emotional terms, and against superficial analyses. This would be very dangerous in the extremely tense situation that we are facing in Mali and other Sahelian countries. Many of the reactions are borne out of extreme concern with the region, and from a genuine sentiment of ‘feeling worried’. The urgency to do something is also big. But who should do something? Who are the right actors to do things and talk with?

Neutrality

People from all ethnic groups, urban and rural, different economic classes were present, joined the marches. It gives an idea of unity. Whereas in written reports it is not easy to avoid to create oppositions. Authors use sentences between brackets to avoid any presupposed biases. It is difficult to be neutral and to try to just describe. The phrasing of the problems by displaced Dogon we met in a village about 50 km south from Bamako towards Bougouni struck me. They refused to accuse the Fulbe, but said it were ‘yimbe ladde’ (people from the bush) they did not know.

Displaced people live on the garbage heap of Faladié, Bamako @Mirjam 2019

We also met Fulbe refugees in dilapidated huts on the garbage heap in the middle of Bamako. They are angry but not angry with a specific ethnic group. They do not really understand what is happening around them. However, following the last attack, these displaced people who have lived through such difficult times start to use a different language acquired from their elites. Especially Fulani elites have been quite vocal in their accusations. After this last massacre they tried to moderate their language but they already aired their emotions in previous interviews and publications on Facebook. The use of the word genocide is no longer taboo and ethnic cleansing also appears in reports.

Multiple Voices

The marches were full of anger and emotions, of course; like the media who reported about them. In one article the number of people in the streets went up to 30,000, others report more modest numbers. In the march in Bamako different reasons and emotions crisscross the street. It is both a cry for peace and the stopping of the awfull violence. It is also a march that protests against the government. Most Malians are appalled and ashamed by this intercommunity violence. They do not recognize themselves in this hatred. Religious, cultural, and political organizations called for the march. Each with their own agenda.

Being connected is important to learn and to link, displaced person in the South charging a battery with solar energy @Mirjam 2019

The people who step in have to be aware of those agendas and let’s hope that they will not be instrumentalized by these organizations. Malians have more than the intercommunity violence to be angry about. The state does not function, schools are closed, hospitals do not function, and many people have difficulties to feed their children more than once a day. This combination will feed the emotions that make the opposition camps to the government stronger and stronger, but that will not be a guarantee to end the violence because they can also be used to scapegoat other groups in society.

We will continue to follow the situation and hope to come up with good analyses. Such analyses can only be multi-vocal. It will take time to understand all the different voices. The problem is that we have no time as the situation is degrading every day.

[1] The research project for which I was in Mali concentrates on the ‘new pastoralists movements’ in the Sahel.

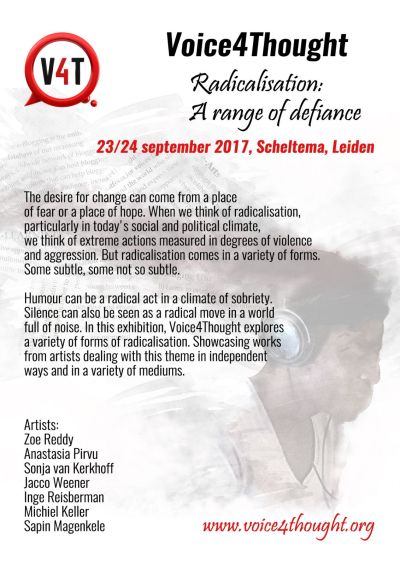

fundamental nature of something, i.e. it leads to change. She questions where the word or concept comes from and what meaning it has gained over time. How has it become equal to violence, extremism in our times? In our present day world we seem to have forgotten about the root meaning of the word. Many people who were radical did bring very positive change. Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King were considered radicals (with a negative connotation) by the regimes in power, but they have changed values in our world deeply and not negatively. In today’s world however radicalisation related to violence and extremism has become a means to create opposition and accuse others of being wrong. It allows those who are in this discourse and reality to define the other as a negative force, whom we need to destroy to make our world safe again. On the other side of this opposition the so-called radicals formulate their own ideologies and have their own reasons to act as they do. In the process they may in the end adopt radical strategies to reach their goals. A concept and the meaning we give it acts, it has consequences in the real world.

fundamental nature of something, i.e. it leads to change. She questions where the word or concept comes from and what meaning it has gained over time. How has it become equal to violence, extremism in our times? In our present day world we seem to have forgotten about the root meaning of the word. Many people who were radical did bring very positive change. Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King were considered radicals (with a negative connotation) by the regimes in power, but they have changed values in our world deeply and not negatively. In today’s world however radicalisation related to violence and extremism has become a means to create opposition and accuse others of being wrong. It allows those who are in this discourse and reality to define the other as a negative force, whom we need to destroy to make our world safe again. On the other side of this opposition the so-called radicals formulate their own ideologies and have their own reasons to act as they do. In the process they may in the end adopt radical strategies to reach their goals. A concept and the meaning we give it acts, it has consequences in the real world.

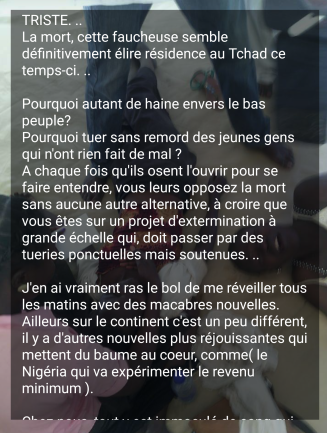

The content of their posts is not only about facts, but as well about the laxity of the Chadian population who they urge to take their destiny in their own hands. A regular commentator is the Strasbourg based journalist Tahirou Hissein Daga. Although the frustration of these Facebook users who find themselves outside the country and feel something needs to change is understandable, the question is if they are justified? What would they do in an atmosphere of fear and intimidation? But also if you live your daily life, does one really see? They are probably not right in the accusation of people who live in difficult circumstances in Chad. Being inside and act is not easy and reminds me of the situation during World War II, with which I opened this blog post. But those who are outside, like the diaspora and hence the international actors, they can see!

The content of their posts is not only about facts, but as well about the laxity of the Chadian population who they urge to take their destiny in their own hands. A regular commentator is the Strasbourg based journalist Tahirou Hissein Daga. Although the frustration of these Facebook users who find themselves outside the country and feel something needs to change is understandable, the question is if they are justified? What would they do in an atmosphere of fear and intimidation? But also if you live your daily life, does one really see? They are probably not right in the accusation of people who live in difficult circumstances in Chad. Being inside and act is not easy and reminds me of the situation during World War II, with which I opened this blog post. But those who are outside, like the diaspora and hence the international actors, they can see!

On Wednesday 1 March, I was shocked by the posts on Facebook about the killing of children in a school in Walia, a southern quarter of N’Djamena; shot by police forces because they were protesting against the arrest on 28 February of 69 young people who were suspected of creating chaos during a campus visit of the Ministre de l’enseignement superieur (Minister of Higher Education) and his Senegalese colleague (25 February); already for a few months the students had protested regularly a.o. against the retreat of their stipends. One form of protest is the molest of government cars; as a student explained to me, this is their only way to express a voice for change. My friends in their thirties remembered this had been their acts as well when they were in college, two decades ago. Arresting these youngsters is not necessary, condemning them even for terrorist acts is worse. On 1 March, the 69 students were condemned for 1 month closed detention for outrage à l’autorité de l’Etat, plus each a ransom of 75 Euros.

On Wednesday 1 March, I was shocked by the posts on Facebook about the killing of children in a school in Walia, a southern quarter of N’Djamena; shot by police forces because they were protesting against the arrest on 28 February of 69 young people who were suspected of creating chaos during a campus visit of the Ministre de l’enseignement superieur (Minister of Higher Education) and his Senegalese colleague (25 February); already for a few months the students had protested regularly a.o. against the retreat of their stipends. One form of protest is the molest of government cars; as a student explained to me, this is their only way to express a voice for change. My friends in their thirties remembered this had been their acts as well when they were in college, two decades ago. Arresting these youngsters is not necessary, condemning them even for terrorist acts is worse. On 1 March, the 69 students were condemned for 1 month closed detention for outrage à l’autorité de l’Etat, plus each a ransom of 75 Euros.

in several towns in this part of Cameroon that were met with violence by the State. Today, 12 December: A call is being made on the internet for declaring a Ghost Town in Southern Cameroon (see Facebook post); what will be the response? The essence of the argument in the protest is the imposition of the Francophone laws, teaching etc. on the Anglophones, a discourse that stands for so much more.

in several towns in this part of Cameroon that were met with violence by the State. Today, 12 December: A call is being made on the internet for declaring a Ghost Town in Southern Cameroon (see Facebook post); what will be the response? The essence of the argument in the protest is the imposition of the Francophone laws, teaching etc. on the Anglophones, a discourse that stands for so much more.

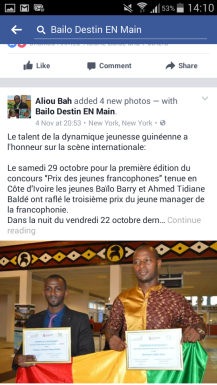

Although some of these young people are from a relatively well-to-do background, most of them are not. They are all part of worlds where it is not easy to make a living, or where most of the youth do not see how to carve out a future. They are on their way to become important people in their societies, representing alternative routes for the youth. This becomes clear from the reception of the two young men from the organization Destin-en-Main in Guinea, and the reflection of the people in Chad on their winning candidate Didier Lalaye on Facebook, on local radio and in the public discourse.

Although some of these young people are from a relatively well-to-do background, most of them are not. They are all part of worlds where it is not easy to make a living, or where most of the youth do not see how to carve out a future. They are on their way to become important people in their societies, representing alternative routes for the youth. This becomes clear from the reception of the two young men from the organization Destin-en-Main in Guinea, and the reflection of the people in Chad on their winning candidate Didier Lalaye on Facebook, on local radio and in the public discourse.