Silenced

I have been silent on this blog for almost a year. A silence shared with my colleague researchers in the Sahel. How can I explain this silence? Are we facing situations for which we have no words? Researchers in the Sahel are confronted with a life-saving reason. They are literally silenced. Speaking out has the risk of being reprimanded, getting difficulties in life, or worse being arrested. For the people about whom I could write I need to be very careful. Those who share information are at risk in the Sahel, targeted from different sides. Exemplary may be the very sad recent death of Sadou Yehia Banandi, after he had given an interview to France 24 about the situation in his region. He was filmed without coverage. The media cannot deny their responsibility.

The death of Sadou shows the risks that are at stake. It is however not only from the Jihadi groups that the risks come. National States increasingly do their best to monitor the outspoken voices. This is also a warning: sharing information in war zones is not without risk, especially for those who are the ‘sources’.

So, I will not share biographies, direct interviews, or detailed reports with the names of those who have given the information. Bibliographies and pictures become weapons for those who want to make others fear their power. I do however, want to share my deep worries for the Sahel. In this short note I share information from Cameroon and Mali/Burkina-Faso.

Violence

The deepest worry is the huge increase in violence since January 2020. Already in 2019 the Niger-BF-Mali region counted 4000 death, of which 1800 in Burkina-Faso. In the period before from 2012 this was 770. In Anglophone Cameroon, since 2017, at least 3000 people have been killed. In the North of Cameroon Boko Haram took also the life of at least 250 civilians in 2019.14 February was a day that will not be forgotten. Ogossagou, a village in Mali where on 23 March 2019 more than 160 people were killed, was again attacked and the number of deaths is unofficially over 40. The explanation for the second attack is found in ethnic violence and the absence of protection in the form of the Malian military, similar to the previous attack. On the same date in Cameroon soldiers massacred at least 23 civilians in a small village in the Bamenda region. They are two, probably heavy, examples of what is happening in the various regions, every day. The violence forces people to flee and the number of refugees and internally displaced people augments to unmanageable proportions.

Oppositions

The violence in both places is of many kinds: attacks of militias; attacks of Jihadists; attacks of military men; intergroup and intragroup violence, interpersonal and gendered violence. Some interpret it in ethnic dimensions. In Cameroon the Ambazonian boys who fight for independence are also fighting in ethnic division. Intragroup attacks, combined with military incursions are the dominant violence. The accusation of the Ambazonian boys of being terrorists makes them prone to laws that give the state a leeway to attack these youth. In the case of Mali/Burkina-Faso exists a strong narrative that Fulani are targeted more than other ethnic groups. This would be the consequence of their alleged alliance with the Jihadi groups who are fighting for the foundation of an Islamic State. It is bad. And it becomes worse with the increasing images of ugly violence. The violence is brutal, dehumanizing, both physically and in words. The people who live these violences search protection that is not given by the state who instead has become part of the violence. Without this protection people will search to legitimize the wars and create discourses to explain why. These are often ethnic oppositions and relate back to interpretations of old (slave) histories, or to occupation of each other’s resources.

Asking attention

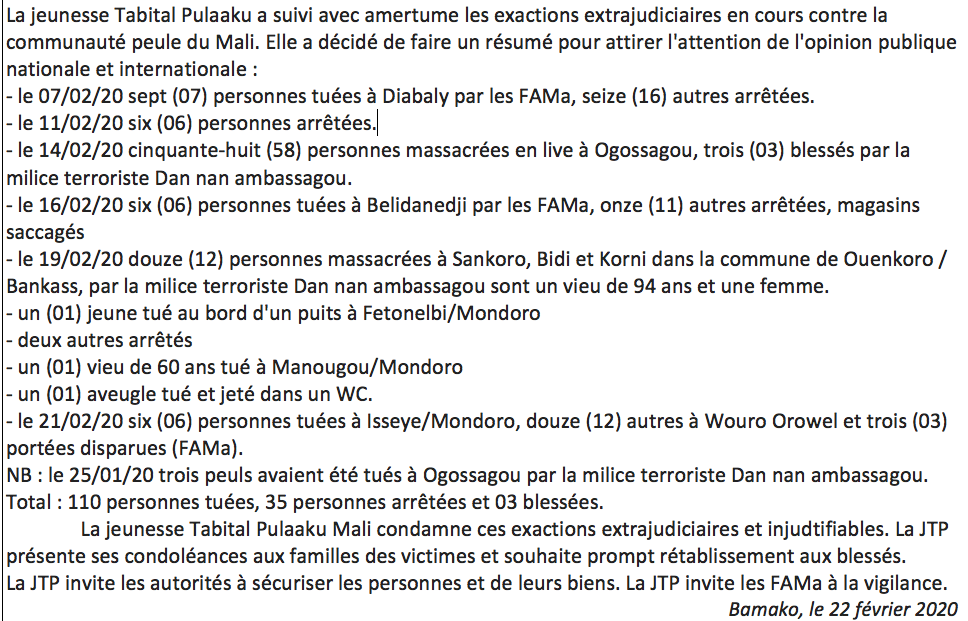

Young people are fighting for attention for the atrocities they see and record every day. They can hardly be outside of the legitimization dynamics. The president of the youth of Taabital Pulaaku, a cultural association defending the culture of Fulani speakers (and as they continue to emphasize, multi-ethnic), expressed their wish to change things by showing the list of attacks from 25 January to 21 February, 2020. Only in these few weeks 110 people were killed, 35 arrested and 3 wounded, all of Fulani descent. The list was sent through social media, together with an audio message in which the list is read by the chair of the youth of Taabital Pulaaku. He is often in the media and does not hide his position.

Whose Responsibility?

The two regions that I presented data of in this blog, are both victim of chaotic warfare, without a clear centre, gradually turning into a civil war dynamic. What some would call ‘new’ wars, in which guerrilla tactics, terrorism and genocide, become central to the war and not the inter-state relations. Ugly violence becomes a weapon in these wars, as the inequality of the forces brings the fighting groups to search for other means. Hence the violence is not of the people, but of those who create the war.

Le Sahel va mal: the population suffers, and creates interpretations of the violences they live, to be able to support the suffering. However, the context of the war, the resource struggles, the world power relations, the international actors (UN, USA, French, EU, G5), the leaders in the Jihadi wars (Islamic State and Al Quaida), the national states, have institutionalised this violence. They have created and perpetuate the ‘violence condition’. Their calls for peace and human rights and the reports that announce the problems, to which I have referred in this blog, are to say the least, very contradictory with their roles in the creation of the violence condition.

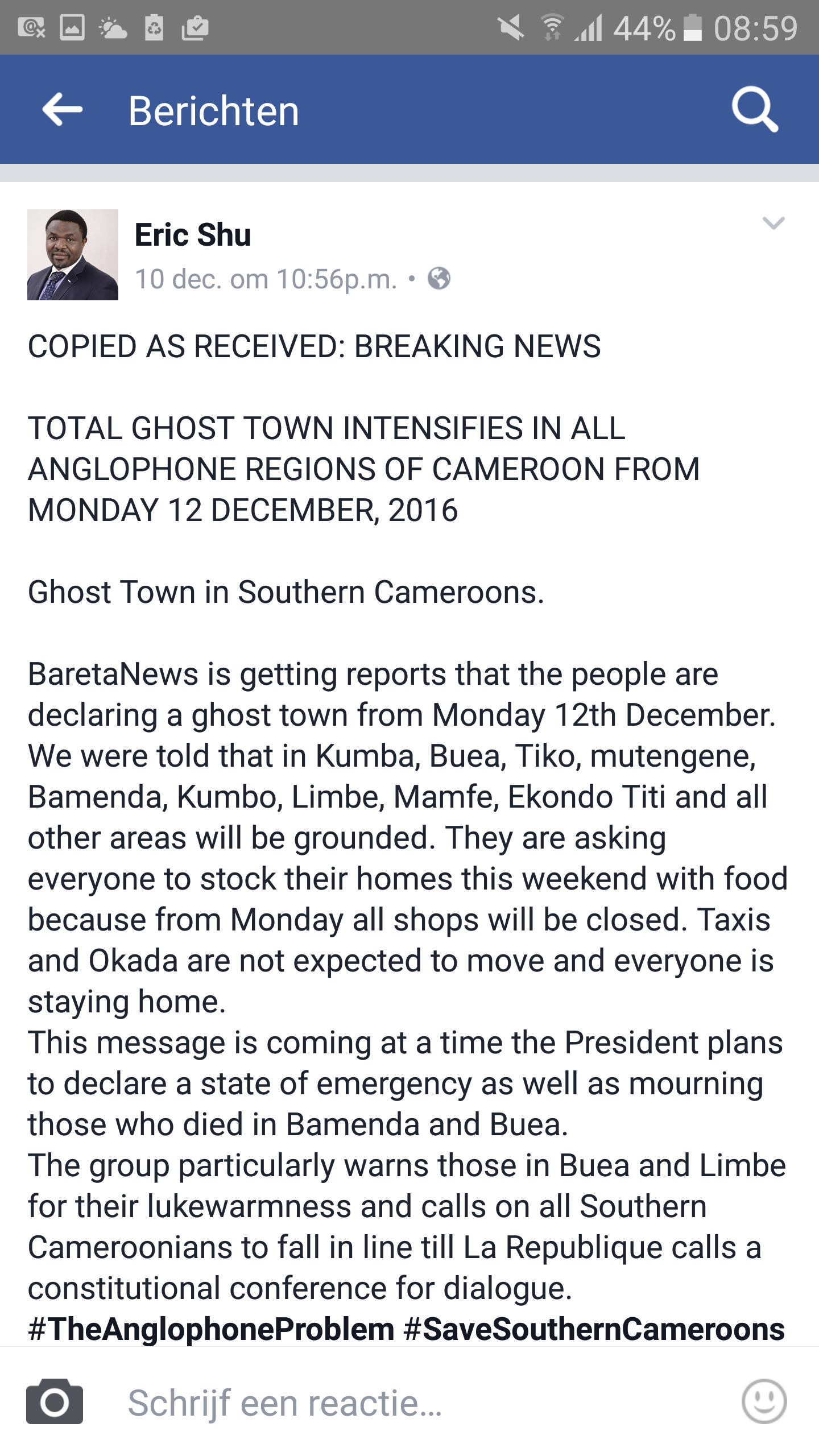

in several towns in this part of Cameroon that were met with violence by the State. Today, 12 December: A call is being made on the internet for declaring a Ghost Town in Southern Cameroon (see Facebook post); what will be the response? The essence of the argument in the protest is the imposition of the Francophone laws, teaching etc. on the Anglophones, a discourse that stands for so much more.

in several towns in this part of Cameroon that were met with violence by the State. Today, 12 December: A call is being made on the internet for declaring a Ghost Town in Southern Cameroon (see Facebook post); what will be the response? The essence of the argument in the protest is the imposition of the Francophone laws, teaching etc. on the Anglophones, a discourse that stands for so much more.

Medicine student

Medicine student