Unequally Glocalised Worlds, Bamenda 2010 @Sjoerd Sijsma

I am in Cameroon, working with Marius, a student from central Africa. Cameroon, Buea, is for him a writing environment. The situation in Bangui does not allow him space to reflect and write. He should have been in the Netherlands. I am here because Marius’ visa for the Netherlands was refused four times over the past year. The repeated reason given at the French Embassy in Bangui: ‘this young man will probably not return to his homeland’. And this is where the story ends and begins. Marius has been accepted as a PhD student at Leiden University, we had produced all letters necessary. There was no reason to not give him the visa. We thought by confidently insisting on his application, and thus repeating it, the Embassy staff would realize their misjudgment. All other diplomatic efforts we tried failed. Marius reflects on it: ‘why do they deny me access to a world where I can learn more? Where I can develop myself into an academic so that I can help my country?’

Humiliation

I could not agree more. It is very unfortunate that the inequalities in our world are played out at this level. Are we not in the right corrupt position? A question that is raised by the recent convocation of the French Ambassador in Bangui, amongst others also for : « délivrance de visas en situation de conflit d’intérêts ».

As the responsible person in the visa demand I feel humiliated and hopeless.. As an academic the only thing I can do is to write and to visualize difficulties and inequalities that are the realities of every day for many young people in Africa, so that others know. One of such realities is Marius’.

Appearances

And Marius is not alone. A Chadian friend told me how, when he went to pick up his visa for the Netherlands at the French Embassy in N’djaména, from all the (mainly) young men only one or two got a visa. His was also refused. Another case where all things were in order with the necessary letters of invitation, return ticket, insurance, but refused on the same grounds. This young artist – Rasta hair – has no fixed income but is always having assignments and is managing his own studio. One can imagine the authorities think: ‘Certainly a youth who wants to stay in Europe.’ He was invited to come to the Netherlands to finalize a film project with his Dutch colleague-cineastes and me. This is a film that might reach out to festivals and critical film competitions. But to get there we need to be able to join forces. The topic of this film is youth and inequality in the world and at home, and the socio-political dynamics this creates. The story of visas should probably be integrated into the project. I will have to travel again to Chad to work on this project; I am not denied a visa: I can freely go were my work and aspirations take me. That is how it should be.

Aspirations Denied

In many African countries we cannot deny that aspirations of young people are killed by the governance systems and economies. Many young men from countries such as the conflict ridden Central African Republic long for a life elsewhere. The images and stories about the ‘other’ world that are circulating on social media are alluring. Why not try? The situation at home is rather hopeless, so it would be good to go out.

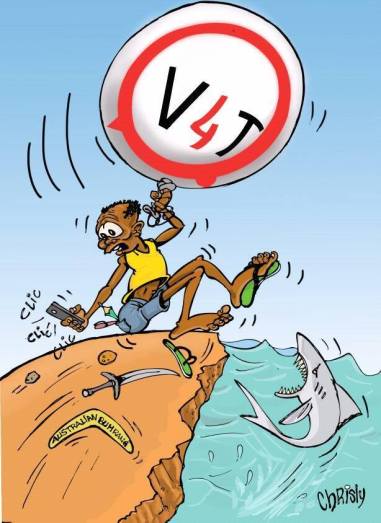

The widespread protests that we see in many countries in West and Central Africa are related to the same feelings of ‘let’s try’. Of course each country has its own special dynamics, political structures, dictatorships and histories of violence, but there is a common denominator. Youth make up more than 60% of the population. Due to the rapid urbanization process the towns become large reservoirs of youth who have left the rural areas, at times forced because their land has been bought by Chinese, European or African businessmen with international relations, transforming the former farmers into cheap wage laborers. Hence, they take on small jobs in the urban economy and enter a new world, including the world of social media.

In some countries, like Chad, there are other ongoing processes that are, to say the least, unjust and incite people to protest. Here, the elites have been stealing from the people for decades while the population suffers from cuts in salary, rising prices, and impossibility to send children to school. Their consequent strikes make the economy even less performing. The poor get poorer and the rich richer.

Escapes?

When I record all this…. it is so logical that protests are rising and youth want to escape their situation. This is the case especially today because we are connected. The Marxist and pan-African writers like Fanon, Aime Cesare and DuBois, and the killed leaders Sankara and Lumumba, are alive again and referred to in Facebook posts. Protests in Africa and attempts by the youth to escape their situation will not stop until the present day leaders are gone, the international community comes to reason and inequalities have reduced tremendously.

Denying visa

Why deny these you men a visa? Do they not have the right to travel, without any explanation? Many of these young people will, like Marius’, come to learn, to work and to discover. Denying a visa to youth who have the right to be mobile is against justice.

On Wednesday 1 March, I was shocked by the posts on Facebook about the killing of children in a school in Walia, a southern quarter of N’Djamena; shot by police forces because they were protesting against the arrest on 28 February of 69 young people who were suspected of creating chaos during a campus visit of the Ministre de l’enseignement superieur (Minister of Higher Education) and his Senegalese colleague (25 February); already for a few months the students had protested regularly a.o. against the retreat of their stipends. One form of protest is the molest of government cars; as a student explained to me, this is their only way to express a voice for change. My friends in their thirties remembered this had been their acts as well when they were in college, two decades ago. Arresting these youngsters is not necessary, condemning them even for terrorist acts is worse. On 1 March, the 69 students were condemned for 1 month closed detention for outrage à l’autorité de l’Etat, plus each a ransom of 75 Euros.

On Wednesday 1 March, I was shocked by the posts on Facebook about the killing of children in a school in Walia, a southern quarter of N’Djamena; shot by police forces because they were protesting against the arrest on 28 February of 69 young people who were suspected of creating chaos during a campus visit of the Ministre de l’enseignement superieur (Minister of Higher Education) and his Senegalese colleague (25 February); already for a few months the students had protested regularly a.o. against the retreat of their stipends. One form of protest is the molest of government cars; as a student explained to me, this is their only way to express a voice for change. My friends in their thirties remembered this had been their acts as well when they were in college, two decades ago. Arresting these youngsters is not necessary, condemning them even for terrorist acts is worse. On 1 March, the 69 students were condemned for 1 month closed detention for outrage à l’autorité de l’Etat, plus each a ransom of 75 Euros.

in several towns in this part of Cameroon that were met with violence by the State. Today, 12 December: A call is being made on the internet for declaring a Ghost Town in Southern Cameroon (see Facebook post); what will be the response? The essence of the argument in the protest is the imposition of the Francophone laws, teaching etc. on the Anglophones, a discourse that stands for so much more.

in several towns in this part of Cameroon that were met with violence by the State. Today, 12 December: A call is being made on the internet for declaring a Ghost Town in Southern Cameroon (see Facebook post); what will be the response? The essence of the argument in the protest is the imposition of the Francophone laws, teaching etc. on the Anglophones, a discourse that stands for so much more.